We are thrilled to have three sociology majors writing honors theses this academic year! Each of these honors students worked with a faculty member in the Sociology Department to conduct research on a sociological topic and write an honors thesis. The students then presented their projects at Brockport’s Scholars’ Day. Here, we highlight each of these honors students and profile the great work they completed in their honors project.

“An Analysis of the ‘Black Lives Matter’ Movement in News Media” by Haley Huey (advised by Dr. Melody Boyd)

The media plays an important role in shaping our perceptions and treatment of others. It is therefore critical to analyze what the media is conveying to its audiences. Using content analysis, this work analyzes news articles written about the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement within a one-year period, between November 1, 2014 and November 1, 2015. A random sample of articles from four news sources, (CNN, Washington Post, Al Jazeera, and The New York Times) was collected, for a total of 160 articles. Quantitative and qualitative content analysis was employed, in which the number of times various phrases and perspectives occurred in the news stories, as well as qualitative examples, were captured. The following two broad, interconnected questions were foundational to this project: (1) What do news articles written about the Black Lives Matter movement express to readership and the public? (2) What does news coverage convey about black lives, police brutality, and the social movement as a whole? Analysis of the overall dataset revealed four main themes in media framing of the Black Lives Matter movement: (1) racial inequality and inclusivity, (2) Policy and political activism as a source of change, (3) violence and the movement, and (4) discrediting the cause. Results include that news media tends to frame the Black Lives Matter movement as a socially diverse agent against police brutality that disproportionately impacts Black men. The movement is also framed as having ambiguous goals for social change, and promoting violence and political correctness.

The media plays an important role in shaping our perceptions and treatment of others. It is therefore critical to analyze what the media is conveying to its audiences. Using content analysis, this work analyzes news articles written about the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement within a one-year period, between November 1, 2014 and November 1, 2015. A random sample of articles from four news sources, (CNN, Washington Post, Al Jazeera, and The New York Times) was collected, for a total of 160 articles. Quantitative and qualitative content analysis was employed, in which the number of times various phrases and perspectives occurred in the news stories, as well as qualitative examples, were captured. The following two broad, interconnected questions were foundational to this project: (1) What do news articles written about the Black Lives Matter movement express to readership and the public? (2) What does news coverage convey about black lives, police brutality, and the social movement as a whole? Analysis of the overall dataset revealed four main themes in media framing of the Black Lives Matter movement: (1) racial inequality and inclusivity, (2) Policy and political activism as a source of change, (3) violence and the movement, and (4) discrediting the cause. Results include that news media tends to frame the Black Lives Matter movement as a socially diverse agent against police brutality that disproportionately impacts Black men. The movement is also framed as having ambiguous goals for social change, and promoting violence and political correctness.

“A Vicious Cycle of Abuse: The Relationship between Domestic Violence and Animal Cruelty” by Leah Staley (advised by Dr. Tristan Bridges)

This Honor’s thesis explores numerous studies on the social relationship between two forms of violence: domestic intimate partner violence and animal cruelty and abuse. It not only depicts that there is in fact a relationship between the two forms of violence but also shows how this topic can be viewed from multiple perspectives. This is a quantitative analysis of past research on this particular topic. It examines what constitutes animal cruelty and domestic violence, what causes people to treat other people and animals in this manner, who are more likely to perpetrators of abuse and also victims of domestic violence, and the different types of mistreatment among abuse animals and people experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV). In addition, this paper examines what kind of laws and services are in place in efforts to combat this issue. Finally, I present resources for those who wish to make a difference and report any cases of cruelty towards people and animals. It is almost certain that if humans hurt other humans, they are most likely harming animals. And if they are harming animals they are more likely to harm humans. Even though most of my research portrays men as more likely to harm other humans and animals, that doesn’t mean that women are not also among abusers. This topic requires further investigation including more variables and better data to get a more accurate depiction on the entire scope of the cycle of violence that not only impacts the victims of cruelty, but society as a whole.

This Honor’s thesis explores numerous studies on the social relationship between two forms of violence: domestic intimate partner violence and animal cruelty and abuse. It not only depicts that there is in fact a relationship between the two forms of violence but also shows how this topic can be viewed from multiple perspectives. This is a quantitative analysis of past research on this particular topic. It examines what constitutes animal cruelty and domestic violence, what causes people to treat other people and animals in this manner, who are more likely to perpetrators of abuse and also victims of domestic violence, and the different types of mistreatment among abuse animals and people experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV). In addition, this paper examines what kind of laws and services are in place in efforts to combat this issue. Finally, I present resources for those who wish to make a difference and report any cases of cruelty towards people and animals. It is almost certain that if humans hurt other humans, they are most likely harming animals. And if they are harming animals they are more likely to harm humans. Even though most of my research portrays men as more likely to harm other humans and animals, that doesn’t mean that women are not also among abusers. This topic requires further investigation including more variables and better data to get a more accurate depiction on the entire scope of the cycle of violence that not only impacts the victims of cruelty, but society as a whole.

“Mass Media and Mass Shootings: The Discrepancies between Workplace and School Shootings” by Nicole Wheeler (advised by Dr. Tara Tober)

Workplace shootings have received very little coverage both in the media and in research. Prior studies have shown that workplace shootings are their own unique entity. Yet, most of the research focuses on mass shootings in schools, or mass shootings in general with little emphasis on workplace violence as a specific form, if any at all. This study compares workplace shootings to school shootings and denotes the similarities and differences between the two both in general and the way they are covered by national news sources like The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, and Chicago Tribune. It covers shootings between 1966 and 2015, and includes 42 workplace shootings and 50 school shootings. Some of the most interesting findings in my research included a higher suicide rate for workplace shooters, higher number of fatalities in workplace shootings, higher number of injuries to victims in school shootings, and the overuse of positive adjectives to describe school shooters by the media when compared with workplace shooters. My findings have led me to believe that the workplace shootings in my dataset were unique in a number of ways compared to the school shootings. Future research should keep this in mind and conduct a more in-depth analysis of this particular type of shooting.

Workplace shootings have received very little coverage both in the media and in research. Prior studies have shown that workplace shootings are their own unique entity. Yet, most of the research focuses on mass shootings in schools, or mass shootings in general with little emphasis on workplace violence as a specific form, if any at all. This study compares workplace shootings to school shootings and denotes the similarities and differences between the two both in general and the way they are covered by national news sources like The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, and Chicago Tribune. It covers shootings between 1966 and 2015, and includes 42 workplace shootings and 50 school shootings. Some of the most interesting findings in my research included a higher suicide rate for workplace shooters, higher number of fatalities in workplace shootings, higher number of injuries to victims in school shootings, and the overuse of positive adjectives to describe school shooters by the media when compared with workplace shooters. My findings have led me to believe that the workplace shootings in my dataset were unique in a number of ways compared to the school shootings. Future research should keep this in mind and conduct a more in-depth analysis of this particular type of shooting.

In describing her experience working on the honors project, Nicole Wheeler stated: “Conducting this research has been one of the most rewarding experiences I’ve had to date. Through the experience, I was able to get to know my professors and thesis director better. It was a rewarding challenge to take on a senior honors thesis, but well worth the time and energy!” We agree with that sentiment and we congratulate all three students on their hard work and insightful research!

By: Tristan Bridges, Tara Leigh Tober, and Nicole Wheeler

Originally posted at Feminist Reflections.

How many mass shootings occurred in the United States in 2015? It seems like a relatively simple question; it sounds like just a matter of counting them. Yet, it is challenging to answer for two separate reasons: one is related to how we define mass shootings and the other to reliable sources of data on mass shootings. And neither of these challenges have easy solutions.

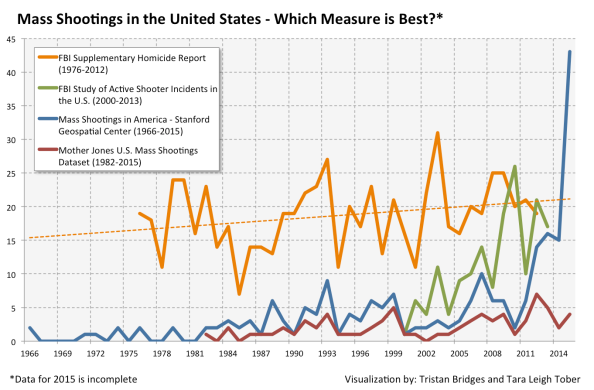

As scholars and teachers, we need to think about the kinds of events we should and should not include when we make claims about mass shootings. Earlier this year, we posted a gendered analysis of the rise of mass shootings in the U.S. relying the Mass Shootings in America database produced by the Stanford Geospatial Center. That dataset shows an incredible increase in mass shootings in 2015. Through June of 2015, we showed that there were 43 mass shootings in the U.S. The next closest year in terms of number of mass shootings was 2014, which had 16 (see graph below). That particular dataset relies heavily on mass shootings that achieve a good deal of media attention. So, it’s possible that the increase is due to an increase in reporting on mass shootings, rather than an increase in the actual number of mass shootings that occurred. Though, if and which mass shootings are receiving more media attention are certainly valid questions as well.

If you’ve been following the news on mass shootings, you may have noticed that the Washington Post has repeatedly reported that there have been more mass shootings than days in 2015. That claim relies on a different dataset produced by ShootingTracker.com. And both the Stanford Geospatial Center dataset and ShootingTracker.com data differ from the report on mass shootings regularly updated by Mother Jones.* For instance, below are the figures from ShootingTracker.com for the years 2013-2015.

If you’ve been following the news on mass shootings, you may have noticed that the Washington Post has repeatedly reported that there have been more mass shootings than days in 2015. That claim relies on a different dataset produced by ShootingTracker.com. And both the Stanford Geospatial Center dataset and ShootingTracker.com data differ from the report on mass shootings regularly updated by Mother Jones.* For instance, below are the figures from ShootingTracker.com for the years 2013-2015.

![]()

For a detailed day-by-day visualization of the mass shootings collected in the ShootingTracker.com dataset between 2013 and 2015, see below (click each graph to enlarge).

The reason for this discrepancy has to do with definition in addition to data collection. The dataset produced by the Stanford Geospatial Center is not necessarily exhaustive. But they also rely on different definitions to decide what qualifies as a “mass shooting” in the first place.

The Stanford Geospatial Center’s Mass Shootings in America database defines mass shootings as shooting incidents that are not identifiably gang- or drug-related with 3 or more shooting victims (not necessarily fatalities) not including the shooter. The dramatic spike apparent in this dataset in 2015 is likely exaggerated due to online media and increased reporting on mass shootings in recent years. ShootingTracker.com claims to ensure a more exhaustive sample (if over a shorter period of time). These data include any incidents in which four or more people are shot and/or killed at the same general time and location. Thus, some data do not include drug and gang related shootings or cases of domestic violence, while others do. What is important to note is that neither dataset requires that a certain number of people is actually killed. And this differs in important ways from how the FBI has counted these events.

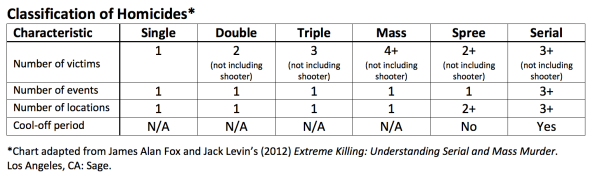

Neither ShootingTracker.com nor the Stanford Geospatial Center dataset rely on the definition of mass shootings used by the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Supplementary Homicide Reporting (SHR) program which tracks the number of mass shooting incidents involving at least four fatalities (not including the shooter). The table below indicates how different types of gun-related homicides are labeled by the FBI.

Often, the media report on events that involve a lot of shooting, but fail to qualify as “mass murders” or “spree killings” by the FBI’s definition. Some scholarship has suggested that we stick with the objective definition supplied by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. And when we do that, whether mass shootings are on the rise or not becomes less easy to say. Some scholars suggest that they are not on the rise, while others suggest that they are. And both of these perspectives, in addition to others, influence the media.

One way of looking at this issue is asking, “Who’s right?” Which of these various ways of measuring mass shootings, in other words, is the most accurate? This is, we think, the wrong question to be asking. What is more likely true is that we’ll gather different kinds of information with different definitions – and that is an important realization, and one that ought to be taken more seriously. For instance, does the racial and ethnic breakdown of shooters look similar or different with different definitions? No matter which definition you use, men between the ages of 20 and 40 are almost the entire dataset. We also know less than we should about the profiles of the victims (those injured and killed). And we know even less about how those profiles might change as we adopt different definitions of the problem we’re measuring.

There is some recognition of this fact as, in 2013, President Obama signed the Investigative Assistance for Violent Crimes Act into law, granting the attorney general authority to study mass killings and attempted mass killings. The result was the production of an FBI study of “active shooting incidents” between 2000 and 2013 in the U.S. The study defines active shooting incidents as:

“an individual actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a confined and populated area.” Implicit in this definition is that the subject’s criminal actions involve the use of firearms. (here: 5)

The study discovered 160 incidents between 2000 and 2013. And, unlike mass murders (events shown to be relatively stable over the past 40 years), this study showed active shooter incidents to be on the rise. This study is important as it helps to illustrate that the ways we have operationalized mass shootings in the past are keeping us from understanding all that we might be able to about them. The graph below charts the numbers of incidents documented by some of the different datasets used to study mass shootings.

Fox and DeLateur suggested that it is a myth that mass shootings are on the rise using data collected by the FBI Supplementary Homicide Report. We added a trendline to that particular dataset on the graph to illustrate that even with what is likely the most narrow definition (in terms of deaths), the absolute number of mass shootings appears to be on the rise. We do not include the ShootingTracker.com data here as those rates are so much higher that it renders much of what we can see on this graph invisible. What is also less known is what kind of overlap there is between these different sources of data.

All of this is to say that when you hear someone say that mass shootings are on the rise, they are probably right. But just how right they are is a matter of data and definition. And we need to be more transparent about the limits of both.

_____________________

*Mother Jones defines mass shootings as single incidents that take place in a public setting focusing on cases in which a lone shooter acted with the apparent goal of committing indiscriminate mass murder and in which at least four people were killed (other than the shooter). Thus, the Mother Jones dataset does not include gang violence, armed robbery, drug violence or domestic violence cases. Some have suggested that not all of shootings they include are consistent with their definition (like Columbine or San Bernardino, both of which had more than one shooter).

This post originally appeared on Feminist Reflections.

By Dr. Tristan Bridges and Dr. Melody Boyd

Both Apple and Facebook recently announced that they will cover egg freezing for their employees. The policies at both companies provoked a series of smart analyses of why they are simultaneously something to celebrate and challenge. For instance, Joya Misra writes, “In an environment in which many women face motherhood and pregnancy discrimination, policies that encourage women to freeze their eggs supposedly to delay parenthood, may actually discourage women from becoming mothers altogether. Access to paid leave and high quality, subsidized childcare would better support women’s decisions about having children” (here). Dr. Misra and others are absolutely correct that egg-freezing policies fail to do anything about the family-friendliness of workplaces and organizations.1 The existing data on people who take advantage of the specific technology Apple and Facebook are offering to cover for female employees, however, suggests that the lack of family-friendly policies is only one issue worth considering here. Among these issues are: cost of infertility treatment, same-sex families, and explorations of the other reasons reproductively healthy heterosexual women might pursue these options.

There are four obvious groups of women who might pursue this technology. The first are queer or lesbian women (see here, here, and here). The second are women with known or anticipated fertility issues (such as cancer treatment). The third group (and those who have received most media attention surrounding this issue) are professional heterosexual women who may be in a relationship, but don’t want to have children until they’ve reached a place in their career where they feel it will be least professionally damaging. The fourth group are single heterosexual women who might pursue freezing their eggs in the hopes of eventually meeting someone. The data suggest that the majority of heterosexual women pursuing this technology are single. As one maternal fetal medicine specialist and Assistant Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology—Dr. Chavi Eve Karkowsky—writes,

“[I]f these women were partnered, but still wanted to delay child-bearing, they would probably pursue IVF with their eggs and their partner’s sperm, and freeze the resulting embryos. IVF and embryo cryopreservation is an older, more refined, and arguably more successful technology… What they want is a baby, yes, but with a willing partner for child rearing and a present father for their child” (here).

What Dr. Karkowsky suggests is that women’s decisions to freeze their eggs might have more to do with not feeling like they’ve found a “Mr. Right” (if they’re even looking for Mr.’s in the first place) than with a desire to focus on their careers. In one study of the reasons women pursue egg freezing as an option, women were asked to select any and all reasons to account for why they had not pursued childbearing earlier in their lives.  While they were allowed to select all of the possible reasons that might apply, only about a quarter of the sample cited “professional reasons” for not having children earlier. The overwhelming majority of women (88%) claimed that “lack of partner” was the primary reason (see our adapted graph).2

While they were allowed to select all of the possible reasons that might apply, only about a quarter of the sample cited “professional reasons” for not having children earlier. The overwhelming majority of women (88%) claimed that “lack of partner” was the primary reason (see our adapted graph).2

This is related to an issue sociologists refer to as the “marriageability” of men. In the context of rising joblessness in low-income urban communities, William Julius Wilson suggested one consequence of shifts in our economy was that poor, non-white, urban men were disproportionately affected by the shift to a service economy. They’re not out of work because they don’t want jobs; Wilson found that they are out of work because the jobs simply don’t exist. And this has reverberations throughout their communities. One consequence was shrinking “pools of marriageable men” for poor black women (here). “Marriageability” has, thus far, largely been discussed as an issue of economic stability (having a job). And, as Kathryn Edin and Maria Kefalas more recently documented in Promises I Can Keep, poor women remain hesitant to bet their futures on men on whom they may not be able to count to provide economically for their families over the long haul.

More recently, Philip Cohen updated the outcome, considering the ratios of employed, unmarried men per unmarried women for black and white women. Cohen’s analysis suggests that poor women still have smaller pools of “marriageable” men, but also that black women face greater shortages of “marriageable” men than white women in most major metropolitan areas. Here too, Cohen relies on Wilson’s formula for marriageability: “marriageable” = employed.

Yet, when middle and upper-class women (the groups most likely to pursue cryopreservation fertility options) are asked why they are pursuing egg freezing, “lack of partner” is highest on the list. But many of these women must live in “partner rich” areas with favorable “pools of marriageable men” as traditionally defined. Surely some of this is the result of women finding men who might qualify as “marriageable” by Wilson’s standard, unmarriageable by their own. As Stephanie Coontz has shown, women and men are asking a lot more out of their marriages today than their parents and grandparents might have. As such, it might not be all that surprising that a more diverse group are delaying and forgoing marriage.  Indeed, as a recent Pew Report investigating the rise in unmarried Americans attests, the population of young adults who have not entered marriage is both growing and changing. For instance, the education gap between never married men and women has widened (see graph). Never married women and men are more educated today than previous generations. More than 53% of never married men today have more than a high school education; 25% have at least a bachelor’s degree. And while it’s a tough economy, Cohen’s analysis suggests that many of these men are finding jobs (often in larger numbers than women in many cities).

Indeed, as a recent Pew Report investigating the rise in unmarried Americans attests, the population of young adults who have not entered marriage is both growing and changing. For instance, the education gap between never married men and women has widened (see graph). Never married women and men are more educated today than previous generations. More than 53% of never married men today have more than a high school education; 25% have at least a bachelor’s degree. And while it’s a tough economy, Cohen’s analysis suggests that many of these men are finding jobs (often in larger numbers than women in many cities).

We suggest that middle- and upper-class women are delaying and foregoing marriage for many reasons, among them that the employed men they encounter are “unmarriageable” for other reasons.

We are currently working on an article collecting research across the class divide dealing with the “marriageability of men” hypothesis. Research shows that the “lack of marriageable men” trend is best analyzed as twin trends occurring among different groups for different reasons. For instance, Wilson suggested that “marriageability” primarily had to do with obtaining a job—a task more difficult from some groups of men than others. But, middle- and upper-class women, by this standard, should be marrying in droves—employed men are not always the issue. Men who might be capable of financially providing are not necessarily all women want out of a relationship today.

For instance, in The Unfinished Revolution, Kathleen Gerson found that men and women across a range of class backgrounds said that they desired gender egalitarian relationships. Men were just as likely as women to say that having a partner able to find personally fulfilling work and to co-provide financially was an important part of what they hoped to achieve in current and future relationships. Things get more complicated, however, when women and men are asked about their backup plans. What happens when those plans for dual-earning, emotionally fulfilling, egalitarian partnerships don’t work out? Women state that they are willing to confront a range of options in terms of fulfilling their family and career goals. Men, on the other hand, are most likely to say that their fallback option does not include the possibility of staying home themselves. Rather, men’s “plan B” appears to put women right back at “plan A” 50 years ago (see Lisa Wade’s analysis here). Indeed, in her interviews with women about their heterosexual experiences in Hard to Get, Leslie Bell finds profound dissatisfaction among 20-something women with their romantic and sexual relationships with men.

While only a small number of women currently choose to pursue oocyte cryopreservation, this issue represents a larger concern with which many women are dealing more generally. Freezing their eggs is one of many strategies heterosexual women might pursue as men are navigating new meanings of what it means to qualify as “marriageable” today.

________________________________

Thanks to D’Lane Compton and C.J. Pascoe for advanced reading and comments on this post.

1 Whether or not assisted reproductive technologies (ART) are covered by insurance also varies by state in the U.S. Some states mandate IVF coverage, for instance, while other states do not. In states that do not mandate coverage, it is a more expensive for employers to include coverage in their employee health benefits packages. So, this is not only an issue of “good” and “bad” companies, but one of state legislation that influences organizational policies as well. See here for state-specific policies.

2 It’s important to note that some social desirability bias is likely to rear its head here. For instance, some respondents may have felt that claiming “professional reasons” for not pursuing childbearing earlier may be perceived unfavorably by others.

by: Tristan Bridges

This fall, we decided to continue a tradition in our department of stressing some basic statistical analysis in our lower-level courses. As a part of that, students in any section of Introduction to Sociology produce a data analysis project that has them rely on a small sample of variables from the General Social Survey to run and interpret a basic crosstabulation. This semester, I decided to try something new in my large lecture course: to teach students about crosstabulation, I had them produce a human crosstabulation using their bodies in the lecture hall (I wanted to do it out in the quad, but called it due to weather).

This fall, we decided to continue a tradition in our department of stressing some basic statistical analysis in our lower-level courses. As a part of that, students in any section of Introduction to Sociology produce a data analysis project that has them rely on a small sample of variables from the General Social Survey to run and interpret a basic crosstabulation. This semester, I decided to try something new in my large lecture course: to teach students about crosstabulation, I had them produce a human crosstabulation using their bodies in the lecture hall (I wanted to do it out in the quad, but called it due to weather).

We started by separating the class into two groups: “traditional students” and “non-traditional students.” The College at Brockport has a large non-traditional student population. So, of the 112 students in my course (on the day of this exercise), I wasn’t surprised to learn that 41 of them classified themselves as “non-traditional.” For our purposes, we defined “traditional” students as 18-22 years old students who started college at The College at Brockport and live on campus.

Once in groups, I asked the students to think about their experience thus far at college. And everyone was asked to rank their satisfaction with their college experience so far as “less than satisfied,” “satisfied,” or “more than satisfied.” Although this is not a representative sample of Brockport students, we pretended that it was for the purposes of our analysis. And we discussed what that meant at the outset. I had students formulate a hypothesis about their perceptions of how student status (traditional or non) might affect how happy students are with their college experience. Everyone came to the same conclusion: the students thought that traditional students would be more likely to be satisfied. Once students had an idea about how satisfied (or not) they were with college, all of them arranged their bodies into a human frequency table. Then—of course—we all took selfies to commemorate the moment and tweeted them out (#drbridgeshumancrosstab).

The lion’s share of the students classified themselves as “satisfied” (93 of 112). 15 students were “less than satisfied” and only 4 students were “more than satisfied.” Of those 15 students who were “less than satisfied,” however, a larger number were non-traditional (9) than traditional (6) college students. We talked about these observed frequencies, discussing the fact that the numbers appeared to loosely confirm our hypothesis. While the raw numbers might look close, only 8.5% of traditional students were “less than satisfied” compared with 22% of non-traditional students. Certainly, it’s a difference. But, is the different large enough—again, pretending that this is a representative sample—to argue that student status is actually causing non-traditional students to have worse experiences? To answer that, we calculated Chi Square and tested our results for statistical significance.

The lion’s share of the students classified themselves as “satisfied” (93 of 112). 15 students were “less than satisfied” and only 4 students were “more than satisfied.” Of those 15 students who were “less than satisfied,” however, a larger number were non-traditional (9) than traditional (6) college students. We talked about these observed frequencies, discussing the fact that the numbers appeared to loosely confirm our hypothesis. While the raw numbers might look close, only 8.5% of traditional students were “less than satisfied” compared with 22% of non-traditional students. Certainly, it’s a difference. But, is the different large enough—again, pretending that this is a representative sample—to argue that student status is actually causing non-traditional students to have worse experiences? To answer that, we calculated Chi Square and tested our results for statistical significance.

Students in each of the cells first calculated what the expected frequencies would have been if student status had no impact on satisfaction with college. We compared these with our observed frequencies and I had students raise their hands if the expected frequency was higher or lower than the observed in the cell they occupied. Then, students in each cell used these two numbers to calculate the test statistic for their cell. We added all of these up to collectively produce a value for Chi Square for the class and compared it to a critical Chi table together.

I’m hoping that the human frequency table made learning something students sometimes struggle with more enjoyable. But, it also seemed like a fun way of reminding students that when they seem tables containing numbers sociologists use to make claims about people and the social world, those numbers are actually referring to people (just like us). So, we all performed a statistical analysis together (all 113 of us) before going online to look at how online modules can help do much of this for us.

I’m hoping that the human frequency table made learning something students sometimes struggle with more enjoyable. But, it also seemed like a fun way of reminding students that when they seem tables containing numbers sociologists use to make claims about people and the social world, those numbers are actually referring to people (just like us). So, we all performed a statistical analysis together (all 113 of us) before going online to look at how online modules can help do much of this for us.

If you’re interested, we did find a statistical relationship between student status and satisfaction with college. And we did not talk about alternative explanations for the finding. It’s not representative data, but it’s an interesting finding.

It’s a project I’m excited to continue in the course. Having better data literacy is something I’d like all of our students to achieve while at Brockport. Part of this involves understanding what the numbers and graphs mean. But, some of it involves an ability to look beyond the numbers and charts to see the people that comprise that data. Next time, I’ll make sure the weather cooperates.

____________

Thanks to Dr. Melody Boyd for enduring some of the exercise and helping me get some “action shots.”

Now that the academic year is over, we thought it would be interesting to profile what some of our faculty do during the summer months. Dr. Boyd is doing fieldwork in Dallas, Texas this summer, and here she tells us about her research.

I am part of the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on How Housing Matters for Children and Families, and am collaborating with a team of researchers doing a two-year qualitative study analyzing the housing decisions that families make. Our goal is to interview families from various income and racial backgrounds to understand how families make tradeoffs when deciding about where to live, and how these decisions affect their children. We are collecting data in Cleveland, Ohio and Dallas, Texas. This is a longitudinal study, which means we are talking to families at multiple points in time to analyze changes over time. We conducted the first round of interviews in the summer of 2013, and this summer we are following up with the families we interviewed last summer.

Last summer I was in Cleveland for two and a half months recruiting families to participate in the study and conducting in-depth qualitative interviews with families. We created a random sample of addresses in various neighborhoods throughout the city of Cleveland and the surrounding suburbs, and from that sample determined which families were eligible for the study. Since this project is focused on the impacts of housing on children, we limited our sample to families who have children between the ages of 3 and 8. Once we determined that a family was eligible for the study we conducted an interview with them, usually in their home. The interviews usually lasted around 3 hours, so we learned a lot from the families! I invited t

Last summer I was in Cleveland for two and a half months recruiting families to participate in the study and conducting in-depth qualitative interviews with families. We created a random sample of addresses in various neighborhoods throughout the city of Cleveland and the surrounding suburbs, and from that sample determined which families were eligible for the study. Since this project is focused on the impacts of housing on children, we limited our sample to families who have children between the ages of 3 and 8. Once we determined that a family was eligible for the study we conducted an interview with them, usually in their home. The interviews usually lasted around 3 hours, so we learned a lot from the families! I invited t wo sociology majors, Anna Sommer-Grohens and Lindsay Stumpf, to come to Cleveland for a short time to participate in the fieldwork and learn about the process of recruiting respondents and conducting in-depth interviews.

wo sociology majors, Anna Sommer-Grohens and Lindsay Stumpf, to come to Cleveland for a short time to participate in the fieldwork and learn about the process of recruiting respondents and conducting in-depth interviews.

This summer I am doing follow-up interviews in Dallas. It’s great to get to know a new city, and there are a lot of aspects about the housing market and neighborhoods that are different in Dallas than Cleveland. Since we are interviewing families again who we interviewed last summer, we are learning about the changes that their family experienced in the last year. For families who moved between last summer and this summer we are able to learn the whole story about how they made the decision to move, and why they chose to move to their new location.  Some families are in the process of moving this summer, and for those families we are collecting observational data by accompanying them on their housing searches and learning about their housing choices while these decisions are being made.

Some families are in the process of moving this summer, and for those families we are collecting observational data by accompanying them on their housing searches and learning about their housing choices while these decisions are being made.

So, there is a glimpse into my fieldwork this summer. I look forward to talking about what I’m learning in classes and conversations in the fall!

The news industry has changed significantly over the past few decades, and not necessarily for the better. With the emergence of digital technology and modern business strategies, the situation has improved only for the CEO’s, while journalists are being sucked dry.

In his article, “Convergence: News Production in a Digital Age,” Eric Klinenberg (2005) discusses his research into the ways the news media industry has changed since the advent of digital technology. He uses in-depth field observation of the company Metro News to analyze the effects that emerging digital technologies and the application of modern corporate convergence strategies have had on individual journalists, the journalistic profession as a whole, and the way news corporations are structured and managed.

Klinenberg discusses the ways that modern business tactics have led to the creation of large media conglomerates, as town newspapers and local television stations are either bought out or undercut by competition. As many of the companies grew larger, including Metro News, they raised funds by offering publicly traded stock, allowing them to grow even more swiftly and buy out more of their local competitors. From that point forward, the large companies were beholden to the profit demands of stockholders, and overall earnings became more important than journalistic integrity. Corporate managers “streamlined” the workforce, “laying off” large numbers of journalists and requiring the remaining employees to fulfill the duties of multiple individuals. All of these are serious problems, Klinenberg assures readers, and they would have been cause for concern regardless, but the advent of digitization intensified the issues dramatically.

Klinenberg discusses the ways that modern business tactics have led to the creation of large media conglomerates, as town newspapers and local television stations are either bought out or undercut by competition. As many of the companies grew larger, including Metro News, they raised funds by offering publicly traded stock, allowing them to grow even more swiftly and buy out more of their local competitors. From that point forward, the large companies were beholden to the profit demands of stockholders, and overall earnings became more important than journalistic integrity. Corporate managers “streamlined” the workforce, “laying off” large numbers of journalists and requiring the remaining employees to fulfill the duties of multiple individuals. All of these are serious problems, Klinenberg assures readers, and they would have been cause for concern regardless, but the advent of digitization intensified the issues dramatically.

With faster communications technology, vast news networks could be overseen from a single headquarters, allowing for further streamlining of the staff and more intense, less individualized micromanaging. At the same time, with more methods of presentation, including television and the internet, the number of tasks that each journalist must perform has increased exponentially, further decreasing the amount of time they have available to work on any given story. The increased workload and lack of commensurate compensation, along with little allowance for journalistic individuality or integrity, has reduced the profession to a terrifying state. The occupation is now consistently ranked at or near the bottom on a majority of popularity opinion polls. Eric Klinenberg shows that these massive media conglomerates are trying to squeeze every possible cent out of the news industry, and in the process they are changing the journalistic profession into demanding, low-compensation menial labor occupation.

If the implications of Eric Klinenberg’s research are fully considered, they paint a bleak picture. News journalism was once a prestigious and highly respected profession, combining the best and brightest writers with skillful interviewers and high work standards for writing and integrity. If the current trend of maximizing profit continues, however, news journalism will be a profession for those who are willing to work long hours for little pay. Also, there are political ramifications to this shift in journalism. The industry is dominated by talking points, with every station recycling the work of their competitors without adding much value. The industry scrutinizes the every action of celebrities because they are popular, and that association with popularity increases sales. Stations are often polarized along political lines, vehemently attacking the opposing party and supporting the party of their corporate owner’s political agenda, regardless of factual evidence. Corporations sometimes pull stories from broadcasts if they conflict too intensely with the party platform, refusing to report on what is actually happening in its entirety. There is a reason that political scientists consider the news organization a political institution, as it is the news industry that the general public relies on to inform us of political issues. The public requires unbiased political reporting so that decisions can be made based upon the facts, rather than upon a skewed representation of reality driven by profit and corporate interests.

–

Reference

Klinenberg, E (2005).”Convergence: News Production in a Digital Age.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 597(1), 48-64.

_________________________

*Benjamin Haskell is a freshman in the Honors Program at The College at Brockport. He is majoring in both Communications (Electronic and Print Journalism) and Sociology. After graduation, he wants to write for a prominent newspaper or magazine, such as the BBC, on the subject of new and groundbreaking technology. This post was originally submitted in Dr. Eric Kaldor’s Introduction to Sociology course (SOC100) in the spring 2014 semester.

Research has shown that men are extremely likely to experience upward mobility in women-dominated professions. But new research suggests that not all men benefit in the same ways.

Nursing is one of the most in-demand jobs in America. As a result of this high demand, many men are seeking employment in the field. And the influx of male nurses has led to a “glass escalator effect.” This can best be described as the advancement of men in both pay and position in jobs dominated by women. Rather than confronting the “glass ceiling” women face in professions dominated by men, research has shown than men’s experiences in women-dominated professions are almost exactly the opposite.  It was thought that this glass escalator offered a “free ride” to all men, but a new qualitative case study of 17 black male nurses by Adia Harvey Wingfield (2009) suggests otherwise. Wingfield found that black male nurses were more likely to experience the “glass ceiling” than the “glass escalator.” In the study, Wingfield conducted semi-structured interviews with 17 black male nurses and sheds new light on racial tensions and inequality in America.

It was thought that this glass escalator offered a “free ride” to all men, but a new qualitative case study of 17 black male nurses by Adia Harvey Wingfield (2009) suggests otherwise. Wingfield found that black male nurses were more likely to experience the “glass ceiling” than the “glass escalator.” In the study, Wingfield conducted semi-structured interviews with 17 black male nurses and sheds new light on racial tensions and inequality in America.

Some of the roadblocks affecting black male nurses are put into stark relief in the interview data she presents. The most intense and difficult roadblock has been “institutional racism”—the system of racial inequality that has become engrained in social institutions (Giddens, et al. 2013, p. 300)—in this case hospitals, health care, and perhaps the economy more generally. Certainly, old-fashioned racism still exists today as well. This can best be explained by one of the black male nurses interviewed. He shared an instance in which he walked in to treat a patient while dressed in full scrubs. Despite his hospital attire, and working with a patient vitals machine, the patient assumed he was a janitor. White male nurses often share experiences of being mistaken for doctors. The idea that black men are better suited for lower-skilled service jobs is common in our society. Clearly Ray was not benefiting from the invisible privileges that seem to work for white men in women-dominated professions.

Another serious roadblock was stereotyping. Black men have long been stereotyped in America as less intelligent, more prone to violence, more sexually aggressive, etc. While we may think of these stereotypes as a thing of the past this was not the case for Ray. Ray recalls an incident where he walked into a patient’s room and began to care for her. When asked by the older white female patient where the nurse was, Ray responded, “I am the nurse.” The patient immediately asked to see “someone else.” Despite what we might want to believe, stereotypes continue to threaten black men, even those in respected professions.

Research like Wingfield’s is important because it shows us that inequalities are institutionalized. Women are often disadvantaged because of their gender. But, we also find that men of certain races are also disadvantaged. The intersection of gender and race form a barrier that prevents fair treatment of many members of society. By analyzing these inequalities, we come to the sobering conclusion that America’s race problems cannot be solved overnight. Rather, it will require a systematic approach of attacking institutionalized forms of racism and recognizing that inequalities are not only perpetuated by racist, sexist, classist, heterosexist, etc.ist people. They get built into the institutions through which we all pass. Wingfield’s research also provides new directions for more research on this topic. What other research can be done? Are all minority men equally unlikely to benefit from the “glass escalator”? Does a man’s sexual orientation have any effect? Would a gay upper-class man experience the “glass escalator,” or would homophobia prevent this? This research also leads us to question if this type of racism is institutionalized in certain parts of the country more than other? Wingfield’s study was carried out in the South, an area many associate with racial prejudice. It’s important research and challenges us to think more carefully about intersections between gender and race when studying contemporary forms of inequality.

–

References

Giddens, A., Duneier, M., Appelbaum, R.P., Carr, D. (2013). Essentials of Sociology. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Wingfield, A.H., (2009). Racializing the Glass Escalator: Reconsidering Men’s Experiences with Women’s Work. Gender & Society, 23. 5-26.

________________________

*Dalton Rarick intends to join the nursing program at The College at Brockport. His interest in sociology stems from a desire to better understand social problems and systems of inequality. This post was originally submitted in Dr. Tristan Bridges’ Introduction to Sociology course (SOC100) in the spring 2014 semester as a project helping students learn more about the process of searching for and evaluating social scientific research.

Pro-marriage initiatives may well perpetuate the cycle of poverty, rather than arresting it.

By: Haley A. Markham*

By: Haley A. Markham*

In 2010, authors Wagmiller, Gershoff, Veliz, and Clements, reported their findings to the query: “Do Children’s Academic Achievement Improve When Single Mothers Marry?” in Sociology of Education. Since maternal marriage is often touted as a panacea for challenges endured by children in single parent homes, the researchers attempted to discern when and if this is so, and to what degree maternal marriage specifically impacts academic achievement, if at all. Their sample included 21,260 children enrolled in 944 kindergartners during the 1998-1999 school year. Data were collected by the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). An average of 23 kindergarteners were selected from each of the sampled schools; their academic achievement was assessed annually using math and reading scores collected through fifth grade. They accounted for variables such as: parental education, financial status, and learning support/enrichment activities provided to the children. Wagmiller, Gershoff, Veliz, and Clements concluded that the benefits of maternal marriage to their children is so limited and circumscribed that federal and state marriage initiatives should be reevaluated for relevancy and appropriateness in the context of social policy.

In 2010, authors Wagmiller, Gershoff, Veliz, and Clements, reported their findings to the query: “Do Children’s Academic Achievement Improve When Single Mothers Marry?” in Sociology of Education. Since maternal marriage is often touted as a panacea for challenges endured by children in single parent homes, the researchers attempted to discern when and if this is so, and to what degree maternal marriage specifically impacts academic achievement, if at all. Their sample included 21,260 children enrolled in 944 kindergartners during the 1998-1999 school year. Data were collected by the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). An average of 23 kindergarteners were selected from each of the sampled schools; their academic achievement was assessed annually using math and reading scores collected through fifth grade. They accounted for variables such as: parental education, financial status, and learning support/enrichment activities provided to the children. Wagmiller, Gershoff, Veliz, and Clements concluded that the benefits of maternal marriage to their children is so limited and circumscribed that federal and state marriage initiatives should be reevaluated for relevancy and appropriateness in the context of social policy.

Beyond the scope of governmental initiatives, this study provides new knowledge about the cycle of poverty. The study itself is hampered, in that there are far too many critical variables not identified or addressed in the data they rely on for their research, such as: siblings and step-siblings and their numbers/ages/genders/birth order/behavioral impact upon the family; extended family and their involvement with the child, including the biological father (if not the man who mother married, if indeed the mother married a man at all!); the neighborhood/school/external support system available to the child; the tangible goods and foodstuffs available to the child, his/her health and access to appropriate care; history of trauma, disability, developmental delays and temperamental variances, the ages of the parents, and their own histories, etc. Given the magnitude and number of such key factors not mentioned in the study, it seems doubtful that a strong correlation could be made between maternal marriage and academic achievement. The study does, however, afford the researchers the opportunity to discern a notable disparity within their sample: while maternal marriage amongst lower income and less educated people seemed associated with lower levels of academic achievement for the reporting child, maternal marriage among higher income and higher educated people seemed to produce a benefit, at least within the limited age range of the sample.

This may suggest that the marriage of two disadvantaged people has the potential to compound problems faced by their children (instead of lessening them, as the social strategists would suggest) whereas the marriage of two advantaged people might enhance their children’s achievements. It is a simplistic hypothesis, but provocative. If this is true—and further research will have to address this—the very governmental initiatives that purport to benefit the poor may in fact ensure that the well-to-do are buffered and the poor remain mired within the confines of the cycle of poverty with the challenges of one generation influencing and compounding the next.

–

Reference:

Clements, M., Gershoff, E., Veliz, P., & Wagmiller Jr., R.L. (2010). Does Children’s Academic Achievement Improve When Single Mothers Marry? Sociology of Education. 83(3), 201-226.

_______________________________________

*Haley Markam is a sophomore recently accepted into the Nursing Class of 2016 at The College at Brockport. This post was originally submitted in Dr. Eric Kaldor’s Introduction to Sociology course (SOC100) in the spring 2014 semester as a project helping students learn more about the process of searching for and evaluating social scientific research.

On April 2, 2014, Jackson Katz visited the Brighton campus of Monroe Community College to discuss masculinities, manhood, and his violence prevention program. Dr. Katz’s books The Macho Paradox: Why Some Men Hurt Women and How All Men Can Help(2006) and Leading Men: Presidential Campaigns and The Politics Of Manhood (2012)address the facets of masculinities in the political arena and in personal lives of both men and women.

Dr. Jackson Katz with Lindsay Stumpf, Sociology department alumnus Tyler Sollenne, and one of our newest majors, Carmelo Crasi.

Dr. Katz began his lecture with a discussion of Women’s History Month and why women need a month to begin with. He then discussed his Mentors in Violence Prevention (MVP) program and how it has been effective in a variety of arenas: sports teams, police departments, and even in the military. Dr. Katz spoke about one of the main problems with ending violence against women—the tendency to use the passive voice when discussing it so that men’s role in it is obscured. Instead of calling it a “women’s issue,” Katz recommends referring to this as “men’s violence.” In this way men will feel that they have responsibility to help end this problem.

The way that Dr. Katz suggests everyone in the audience can help end this violence is through addressing the role of bystanders. Instead of focusing on the victims or perpetrators, Dr. Katz believes that equipping those around a situation with the tools to confront someone for sexist remarks and behavior or to intervene in a negative or dangerous situation is a way that violence can be prevented before it occurs. Jackson Katz talked about men as a “default setting”—one to which we do not pay attention (similar to whiteness or heterosexuality). It reminded me of Michael Kimmel’s article, “Invisible Masculinity” that we read and discussed in my Sociology of Men and Masculinities course taught by Dr. Bridges last spring (2013). The privileged group rarely has the experience of being reminded of their status or having to compensate for it.

Because men are given privilege in our society, Dr. Katz mentions that it is especially important for men to speak out against men’s violence. Although women are the group that receives the most attention as victims of violence, Dr. Katz reminded the audience that many men can be raped or beaten by partners, that many boys as well as girls grow up seeing their mothers beaten by their husbands or boyfriends, and that even when men do not experience violence firsthand, many have had to deal with the aftermath of violence in their relationships with women who have. Another reason that Dr. Katz mentioned it is important for men to speak out is because of the tendency for society to “shoot the messenger” when women attempt to raise awareness for men’s violence. Women who champion equal rights and safety are often called slurs such as “bitch”, “feminazi”, and “manhater.”

Dr. Katz ended the night with some humorous clips depicting a not so humorous topic—street harassment. Street harassment and catcalling are ways that women are made to feel unsafe, and are one of the overlooked ways that men can intervene in the harassment and violence directed towards women. What seems like a harmless compliment or friendly banter can actually cause stress and fear in women who are unsure of a man’s intentions. Overall, Dr. Katz’s lecture was a wonderful introduction to thinking more critically about the relationship between men, masculinity and violence as well as rape culture, the bad reputation of the “f” word (feminism) and the bystander approach towards preventing violence. If more men can be made aware of their potential to help stop violence, both men and women can live happier and safer lives.

_________________________________

Lindsay Stumpf is a graduating senior at The College at Brockport. She is majoring in Sociology with a minor in Women and Gender Studies. As a member of the Honors Program, Lindsay is also completing a senior thesis addressing representations of masculinity in children’s cartoons under the guidance of Dr. Melody Boyd. Lindsay was recently admitted into the Public Administration program for graduate study at The College and Brockport. She starts in the summer of 2014.

I recently came across a calendar from a safety supply company: Condor. It depicts workers in various occupations, from construction to dentistry. Most of the images depict manual-labor jobs (lifting, working with hazardous chemicals, or operating dangerous machinery). The small sample of images speaks to the ways in which we rely on simplistic categorizations to share messages about safety through commonly-held beliefs about who will need it most.

In Kris Paap’s book, Working Construction: Why White Working-Class Men Put Themselves – and the Labor Movement – in Harm’s Way, she explores gender and racial inequality in construction jobs. The calendar’s lack of racial diversity (only three minority groups are depicted) helps to illustrate some of Paap’s findings. Women and racial minority groups are subtly discouraged from participating in this work setting, limiting their options for employment prior to a fair assessment of their abilities. In addition, this discussion contributes to the idea that masculinity – as with gender – cannot be easily defined. It’s situational, location-sensitive, and always in flux.

In Kris Paap’s book, Working Construction: Why White Working-Class Men Put Themselves – and the Labor Movement – in Harm’s Way, she explores gender and racial inequality in construction jobs. The calendar’s lack of racial diversity (only three minority groups are depicted) helps to illustrate some of Paap’s findings. Women and racial minority groups are subtly discouraged from participating in this work setting, limiting their options for employment prior to a fair assessment of their abilities. In addition, this discussion contributes to the idea that masculinity – as with gender – cannot be easily defined. It’s situational, location-sensitive, and always in flux.

The most interesting of these twelve calendar images is the one that depicts a woman wearing safely glasses. Even though she is pictured in the calendar with men working various manual-labor jobs,  this image does not show the advertised safety gear in motion and, in fact, the description under this woman speaks not of safety from harsh conditions, but only about the customized lens colors. It reads, “choose from various lens colors and anti-fog or scratch-resistant coatings.” While most of the images in the calendar speak of “high-impact” protection and using safety to “improve productivity,” only three of the twelve images reference color as an important factor to the gear itself.

this image does not show the advertised safety gear in motion and, in fact, the description under this woman speaks not of safety from harsh conditions, but only about the customized lens colors. It reads, “choose from various lens colors and anti-fog or scratch-resistant coatings.” While most of the images in the calendar speak of “high-impact” protection and using safety to “improve productivity,” only three of the twelve images reference color as an important factor to the gear itself.